ABOUT

New Jersey’s historian John T. Cunningham called Hudson County a “mantle of wheels” for its central role in transportation history. Now outdated infrastructure can meet 21st-century needs.

The History

Stagecoaches, ferries, canals, and trains made Hudson County key to an early transportation network focused on the port of New York.

The first steam ferry service in the world began in 1812 when Robert Fulton traveled between Jersey City and Manhattan.

In the 1830s, the Morris Canal brought Pennsylvania coal into Jersey City. One of the earliest railroads in the country, the New Jersey Railroad, was also established.

Emergent regional railroads, grown powerful through takeover, lease, and aggregation, competed for access to New York. These lines changed the shape of Jersey City, cutting through the Palisades, filling in marshes, running tracks over city streets. Railyards covered the waterfront. The Pennsylvania Station here was at one time the largest in the world.

The PRR in Jersey City

The Pennsylvania Railroad was a large presence in Jersey City for more than a hundred years. It dominated the waterfront, changed the landscape, and especially shaped the Downtown neighborhoods.

Because the Hudson River was a great barrier to rail, early stations serving New York were built in Jersey City. The second Pennsylvania Station built at Exchange Place, Jersey City, in 1891 was the world’s largest terminal, and enabled passengers arriving by rail to move directly onto ferries without going outside.

The Harsimus Branch freight way (c. 1877) diverged from the PRR main line at Waldo Avenue to better handle burgeoning freight into Harsimus Yards. Embankment construction 1901-5 expanded its capacity.

After 1910, when Pennsylvania Station opened in New York, Jersey City passenger service dwindled. Freight also declined. In 1946, the PRR reported a loss in revenue for the first time. By 1963 the Exchange Place terminal was demolished. The grand Beaux-Arts New York station suffered a similar fate, but its loss sparked preservation activism that has extended to other historically significant PRR sites, including the Harsimus Branch.

Nation's Largest Terminal

The Pennsylvania Station was an intermodal passenger terminal, part of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s holdings on the Hudson River in Jersey City. The terminal was located on the 1812 site of the first landing of the first steam ferry service in the world, and at which rail service began in 1834. The station was the terminus of the PRR main line running down Railroad Avenue, now Christopher Columbus Drive, to what is now Exchange Place.

In 1873 the railroad terminal was damaged by fire and the PRR hired Architect Charles Conrad Schneider to design a grand and elaborate replacement. Modeled after a terminal in Frankfort am Main, Germany, the seven-story Pennsylvania Station was built in 1891 and completed in 1892. It was the largest terminal in the United States at the time. The arched roof of the building had a single span of 250 feet.

New York City Tunnel

The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) consolidated its control of railroads in New Jersey with the lease of United New Jersey Railroad and Canal Company in 1871. At that time PRR considered a proposal for a bridge to Manhattan but rejected it. An alternative was to tunnel under the Hudson River, but tunnels were not feasible for steam locomotives. The development of the electric locomotive at the turn of the century made a tunnel practical. In 1901, PRR President Alexander Cassatt announced a plan to enter New York City by tunneling under the Hudson and building a grand station on the West Side of Manhattan south of 34th Street.

The 1910 opening of the PRR tunnels led to a substantial reduction in PRR traffic to Jersey City. In 1911, the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad, a rapid transit system, began operating over the PRR line west of Waldo Yard, connecting with the new Manhattan Transfer station at Harrison. Ferry service at the Jersey City terminal ended in 1949 and the last PRR passenger train used used the main line to Exchange Place in November 1961.

Public Transit Connections

After the turn of the 20th century, electric trolley cars owned by the Public Service Company ran from the Pennsylvania Station at Exchange Place in Jersey City, taking passengers south to Bayonne and to other parts of Hudson County. The Public Service depot was next to the Pennsylvania Railroad ferry slip, had a large covered shed, and sheltered several trolley lines for the city. This public transportation infrastructure was critical to support the sharp growth in Jersey City's population, largely fueled by immigration, at the time.

A century later, Jersey City is experiencing similar population growth. Public transportation plays a critical role in supporting this growth. Jersey City has already re-introduced electric light rail to its urban infrastructure. It is critical that Jersey City keeps in place historic railroad rights-of-way in order to enhance current and accommodate future public transportation options.

Lay of the Land

The Harsimus Branch and other rail lines terminated along low-lying Jersey City waterfront. By 1870 much of this area was filled in to accommodate the lines and associated warehouses, stockyards, and industries. As shown in adjacent maps, the city’s coastline was drastically changed in a short period of time.

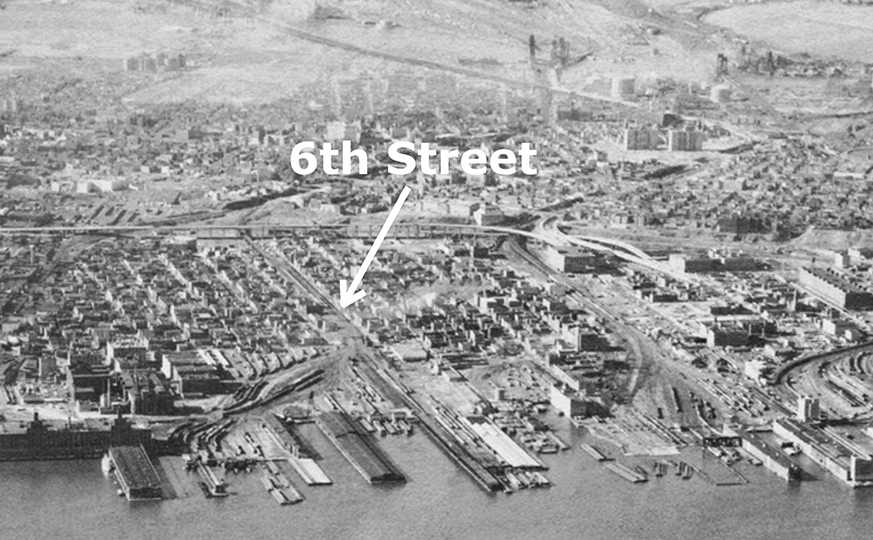

Three elevated lines rose over Downtown Jersey City streets to address changes in topography and to protect the public from trains running at grade. These lines defined Hamilton Park, Harsimus Cove, and Van Vorst Park neighborhoods. From north to south were the Erie at 10th Street, the Pennsylvania Railroad Harsimus Branch at 6th, and the main line of the Pennsylvania at Rail Road Avenue (now Christopher Columbus Drive). The Harsimus Yards lay between the two PRR lines.

The Harsimus Branch was almost at grade at the Hudson waterfront, rising from 13 to 27 feet on the Embankment segments on 6th Street, continuing on trestles until the tracks reached an abutment on the Palisades, then running at grade at the edge of the Harsimus Cemetery, gradually descending into the Bergen Cut near Waldo Avenue.

Harsimus Yards

The Harsimus Yards occupied filled-in land along the Hudson River, beginning at the north where the Erie Yards ended and extending south to Exchange Place. The Harsimus Yards have been entirely replaced by a mixed commercial/residential redevelopment project. North of the Harsimus Yards, the Erie Railroad Yards have also been entirely replaced by residential/commercial redevelopment.

The population of Jersey City increased from 82,546 in 1870 to 206,433 in 1900 (Condit, 1981, p. 373), with much of this increase attributable to European immigration. Some 800-plus workers were employed at the Harsimus Yards at its peak; this number may have been possible because of European immigration. At a time when most people walked to work, it must be assumed that an increasing portion of the local population worked at the nearby Yards, or at the rail-related warehouses and express companies in the adjacent Warehouse district.

6th Street Embankment

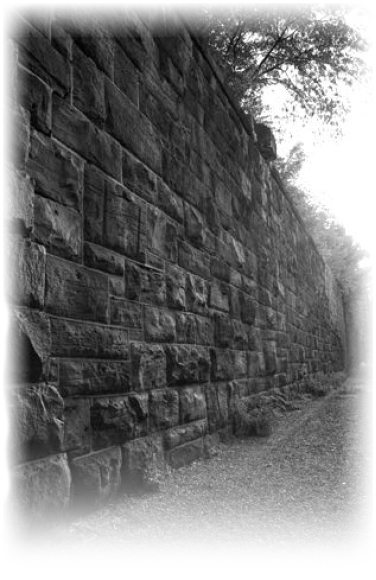

The Embankment is the massive stone section of the Harsimus Branch running parallel to 6th Street in Jersey City. The Embankment comprises six segments extending from Brunswick Street on the west to Marin Boulevard on the east, where its seven tracks became five and turned south to run into the Harsimus Yards.

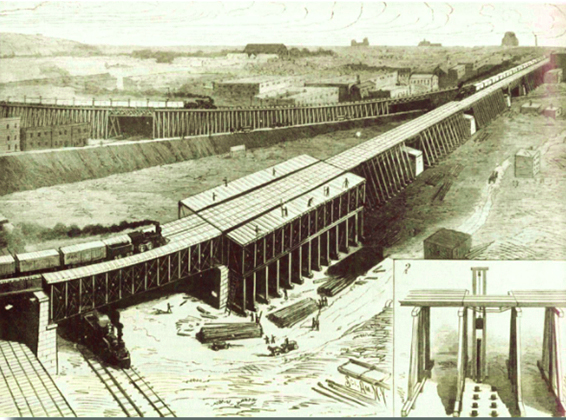

The Embankment replaced an earlier elevated iron freight way that was planned in the late 1860s and constructed in the mid-1870s. Contemporary accounts indicate that the iron freightway was used in the Embankment's construction, and that rail service to the Harsimus Yards continued throughout the period of construction. Quite possibly part or most of the freight way was left within the earthen fill.

Today the Embankment bridges spanning the avenues are gone, but the segments are largely intact.

Trestles

Iron trestles supported by stone stanchions or piers carried Harsimus Branch freight trains from Jersey City’s Brunswick Street, where the stone Embankment ended, to Newark Avenue, then across Newark past Mary Benson Park. The trestles reached an abutment on the Palisades just east of the Harsimus Cemetery. Tracks then ran at grade until meeting the Pennsylvania Railroad main line in the cut below Waldo Avenue.

The adjacent drawing shows the new stone stanchions of the Harsimus Branch. The Harsimus Branch trestlework (foreground) is being replaced by iron deck trusses. In the background is Branch No. 6 of the New Jersey Junction Rail Road. It joins the Harsimus Branch just beyond the Newark Avenue under-grade crossing (upper right). Source: Scientific American 1888)

The trestlework has been removed. Today many of the stone stanchions remain along the edge of Mary Benson Park. The Embankment Coalition proposes to use the stanchions and right of way for an aerial trail that would connect to Waldo Avenue. This trail would also link with the existing River Line trestle crossing Newark Avenue and heading toward the Bergen Arches/Erie Cut, to continue the East Coast Greenway off-road route through Jersey City.

Palisades

Moving east to west, the Harsimus Branch in Jersey City exited the trestle portion via an abutment on the Palisades just east of the Harsimus Cemetery. Two tracks ran at grade behind the Cemetery, gradually descending to an area in the Bergen Cut where the PATH system now has extensive tracks and Conrail maintains one track.

Much of the rail infrastructure on the Palisades is now gone, but the right of way is still visible. Some culverts and catenary supports are still extant, and remains of a switching system. The area is increasingly heavily forested. Invasive bamboo has made a section virtually impenetrable.

The Embankment Coalition proposes to connect the residential part of Waldo Avenue via trail to the Harsimus Branch going east and to the River Line trestle in the direction of the Bergen Arches/Erie Cut – part of the future route of the off-road East Coast Greenway.

Nature Moves In

As rail slowed and then ended on the Jersey City Harsimus Branch, nature began to colonize the line, especially on the Palisades and in the deep soils of the Embankment.

Over the last decades the stone Embankments, isolated above the neighborhoods below, were largely un-touched by humans. Completely natural meadows appeared and a forest matured within a dense urban context.

The natural forest's existence is unique in the world, with an ecology that is place-specific to Jersey City. The Embankment Coalition proposes to study flora and fauna there and remove some invasive plants that are destructive to the stone walls. A trail running through this scape will have a porous surface, allowing stormwater to continue to percolate while minimally interfering with plant growth. The ecology that established itself will require no human maintenance to survive while providing habitat and a green oasis within densely populated Jersey City.

End of the Line

After rail traffic on the Harsimus Branch ended, tracks from all Embankment segments and trestles to the west were removed, as well as most signaling, switching and watering systems. Regularly spaced metal flats remain attached to the upper surface of the coping along much of the northern Embankment retaining wall. All plate girder bridges joining the Embankment segments were removed in 1996 and chain link fencing was attached to the coping at north-south cross-streets.

The right-of-way is still clearly delineated, however, and enjoys protections through its eligibility for the State and National Registers of Historic Places, as does the Embankment structure. When Conrail sold a segment of the Branch in 2005, the Embankment Preservation Coalition joined with the City of Jersey City and Rails to Trails Conservancy in litigation aimed at preserving the historic Branch for public uses of rail, trail, and open space.

Recognitions

Government agencies and other organizations have formally recognized the merits of the Harsimus Branch and Embankment.

1999

State Register of Historic Places

2000

National Register of Historic Places (determined eligible)

2003

Jersey City Municipal Landmark

2004

Recommended segment of East Coast Greenway

2005

Preservation New Jersey's "New Jersey's 10 Most Endangered Historic Sites" list.

Priority Acquisition, Hudson County Open Space & Recreation Plan

Highest Priority Acquisition Site, NY/NJ Harbor Estuary Habitat Program

2006

Jersey City Municipal Landmark (re-designated)

2009

Historic right of way needed for multiple uses, Jersey City Master Plan Circulation Element

2011

National Trust for Historic Preservation "This Place Matters" national challenge, 7th place

2013

Entire Harsimus Branch (Marin to Waldo) right of way and associated sites eligible for National Register of Historic Places – NJ State Historic Preservation Office Opinions

2019

NJ State Historic Preservation Office issues Opinion that the Village area is an Italian Village Historic District and its boundaries encompass the Harsimus Embankment, a contributing element.

Embankment Preservation Coalition

Our Background

The Embankment Preservation Coalition formed in 1998 as a working group that evolved from meetings of more than a hundred neighbors concerned about a proposal to demolish the Harsimus Branch Embankment and develop the site, which is located in Downtown Jersey City and forms the boundary of two National Historic Districts.

The group spent months researching the historic, environmental, aesthetic, and cultural aspects of this structure. Findings led to a consensus that the Embankment is an important and irreplaceable historic, environmental, and transportation resource that must be preserved. A nonprofit organized in 1999 to preserve the Embankment structure and reuse the Branch for multiple public purposes.

Withdrawal of a City redevelopment plan to demolish the historic structure

Documentation of the history and present contribution of the structure to the integrity of two National Historic Districts

Nomination of the site for historic status at the state, federal, and city levels. This nomination was reviewed and approved by the State Review Board for Historic Places, the Jersey City Historic Preservation Commission, the Jersey City Planning Board, the Jersey City Municipal Council, and Mayor Glenn L. Cunningham. The Embankment was listed in the State Register of Historic Places in 1999, determined eligible for listing on the National Register in 2000, and was declared a Municipal Landmark in January 2003. Following a court challenge, it was once again landmarked in 2006.

Endorsements from community, citywide, regional, and national organizations and elected officials at all levels of government

Site cleanups, tree plantings, tours, talks, and other events – with the participation of hundreds of adults and students

Draft designs for a street-level promenade along the base of the Embankment on Sixth Street to link up with the Hudson Waterfront Walkway

Coordination with Newport Associates and Avalon Cove developers on design for public access to the Hudson Waterfront Walkway at the eastern end of Sixth Street

Embankment designation by the East Coast Greenway Alliance as part of the East Coast Greenway main route through Hudson County. The East Coast Greenway is a 3,000-mile National Millennium Trail extending from Florida to Maine; it is about 60 percent complete in New Jersey. Segments of the off-road trail exist in Jersey City and an entire interim trail is also designated and has signage.

Identification of historic site, open space and transportation funds available from the state or federal governments or from private sources for acquisition, improvement, and maintenance of the site

An earmark, sponsored by Congressman Robert Menendez, in the SAFETEA bill that passed Congress in July 2005

Identification of development costs for 6-acre park and greenway, including ADA-compliant access, fencing, bridges re-connecting blocks that can hold emergency vehicles, landscaping, lighting and amenities.

Work with City-hired T&M Associates to refine development costs

Preparation to promote wide and deep public input into park design, once property is acquired

Presentation of objector's case before the Zoning Board of Adjustment that resulted in denial of demolition permits for the Embankment

Pursuit of historic and environmental protections provided by federal railway abandonment law

Litigant, with allies City of Jersey City and Rails to Trails Conservancy, over status of Harsimus Branch. Our claim that the Harsimus Branch is a regulated rail line with protections for the public interest prevailed in federal courts. All litigants are now poised to settle the litigation, subject to government approvals.